Designing while Black: Exploring the evolution of Black Prairie design aesthetic

Why is it so hard to see the Black designing mind?

This story is part of the Black on the Prairies project, a collection of articles, personal essays, images and more, exploring the past, present and future of Black life in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Enter the Black on the Prairies project here.

This Analysis piece was written by Bertrand Bickersteth, who lives in Calgary, teaches at Olds College and writes about Black history in Western Canada.

Green Walters is an oddity. At least that is how he is described by his contemporaries.

He came to Alberta in 1881 and, like most uneducated Black men of the era, found himself taking a stab at whatever opportunity he could find. Walters was what we might today think of as a serial entrepreneur.

He tried his hand as a hay contractor, a ranch hand, a cook, a servant and a cleaner. In some of these roles, his skills were considered less than desired. A. E. Cross, who would become a senator, said that as a cook Walters was neither "methodical" nor "clean."

By all accounts, Walters was odd-looking, too. He was short (called "squat") and had a look that one observer called "extraordinary." Despite his eccentricities, everyone agreed on one thing: he was an excellent entertainer.

"[H]e sang plantation and other minstrel songs all the time and kept us in roars of laughter," said one J. L. Douglas.

Even 120 years ago, the performing role of Black people was an established and welcome stereotype.

'Black people have been put into a box'

Why is it so hard to see Black braininess? Or the Black designing mind?

Tosin Odugbemi is a Harvard-educated visual designer from Edmonton whose understanding of Green Walter's stereotyped role is pointed.

"Black people have been put into a box. We have been viewed as aggressive and simple for years," Tosin said. "Our value has been reduced to existing only to make white people's lives more enjoyable."

This much is clear in history. Again, speaking of Green Walters's comic impact, J. L. Douglas points out "the more we laughed the funnier he became." What's funny is that he never wonders at the simplicity of Walters's response, or what it must have been like to be Black, both surrounded and exposed by an othering gaze out on the open prairie of whiteness.

Here in the 21st century, Tosin's work couldn't be any further from this box confining Black people to simpletons and servants. Unlike Walters, the impact of the exposing prairie gaze on her designing mind is clear. Her work regularly responds.

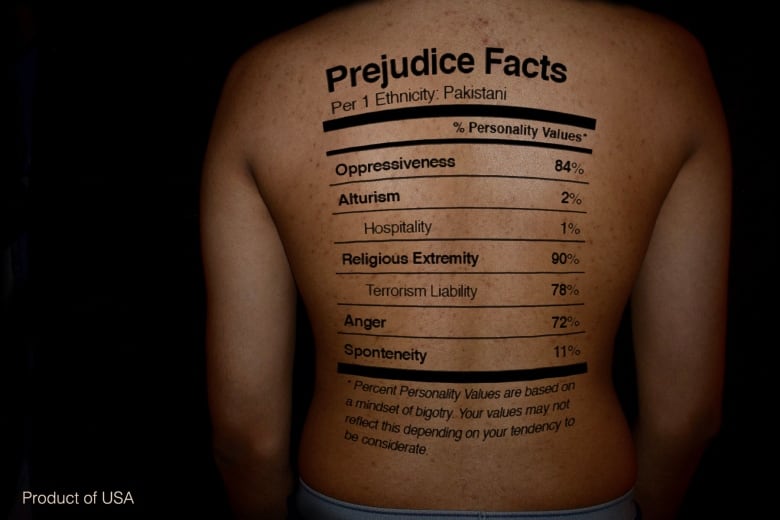

One piece repositions Damien Hirst's works with a Black woman's body. Another reimagines architectural space in response to PTSD suffered by its inhabitants. Yet another literally exposes the backs of racialized people, revealing content labels of a would-be racist gaze.

What would Walters's laughing men have made of the designing mind of this 21st-century Black woman from Edmonton?

Cutting-edge invention

The stereotypes of racism are not hard to trace through time. If Walters's contemporaries were swayed by the false scripts of Black inferiority, Sylvester Long's entire life was defined by running from them.

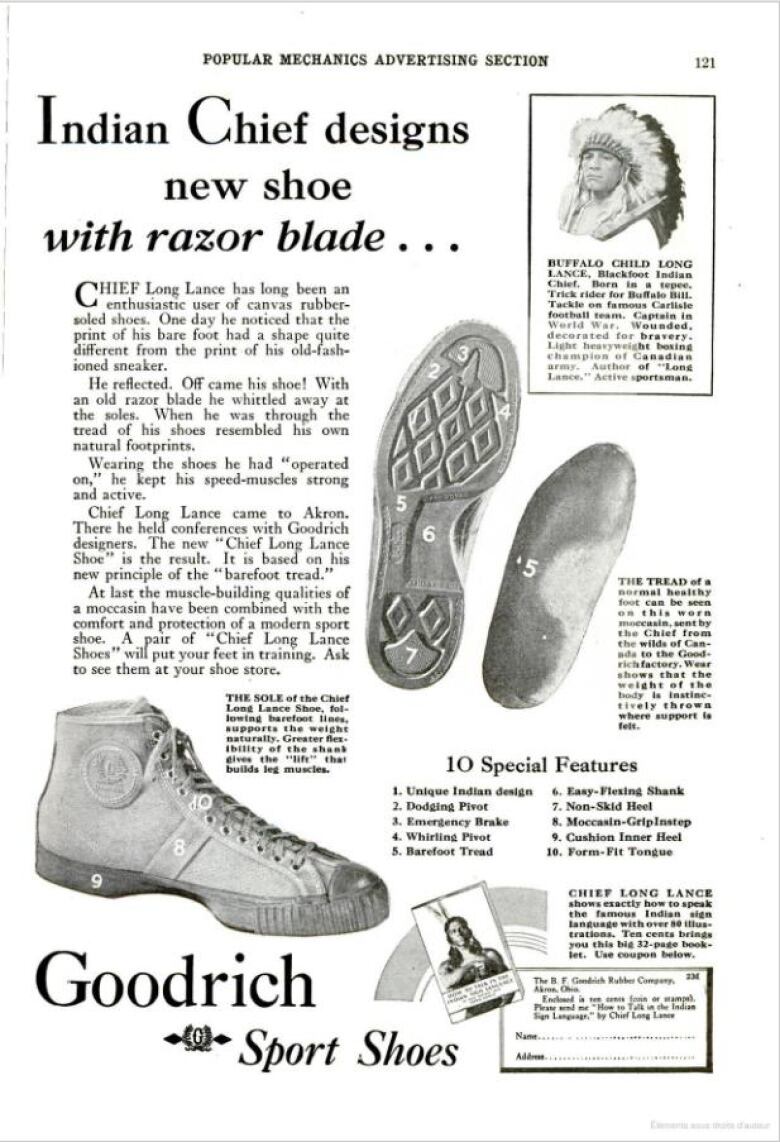

Raised in a Black community, stifled by Jim Crow in North Carolina, Long claimed Indigenous identity as a youngster and ran away with the circus. Years later, he found celebrity repping for the Piikani people of southern Alberta as Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance and sold a best-selling "biography" of his so-called Blackfoot life.

What could be better for this serial escape artist than to design a running shoe? In 1930, the B. F. Goodrich Rubber Company released the Chief Long Lance Shoe, claiming he designed it with a razor blade. Though Green Walters had died by then, he surely would have sympathized with Sylvester Long's cutting edge invention (and reinventions).

Walters, too, was always running. He didn't last in Alberta. After an incident of frost-bitten feet, he packed it in and fled to the U.S. He ended up in Kansas City, right back on prairies.

The importance of knowing

I wish I had known about Green Walters when I was growing up: his layered laughter, his no-nonsense way of mashing potatoes with his fists. It would have made a huge difference to me, not to mention the attitudes I regularly had to confront.

As a nine-year-old, the words "underground railroad" held a mystique I unconsciously transferred to Edmonton's brand new LRT line. Without knowing the history of slavery, trains quickly became a symbol of magical escape for me.

But as a teenager in Calgary, the joys of my childhood memory evaporated. I was regularly targeted at CTrain stations by peace officers questioning my presence and drug dealers sending me surreptitious signals I found baffling.

I grew to dislike the confusion that these spaces forced me into. My gaze became guarded. My hood, a protective shield. I felt always on the verge of being exposed as an outsider and expelled.

Perhaps, I should have learned to play along, or even make them laugh as Green Walters did. It doesn't seem likely that Walters's 19th-century tools could have done the trick in my 1980s reality, but here's something that could have: knowing Walters had existed.

Why is it so hard to see Black braininess? Or the Black designing mind?- Bertrand Bickersteth

Would it have mattered to me that Calgary's CTrain was designed by a Black engineer? Should it matter to anyone?

Oliver Bowen was the engineer in charge of the design and construction of Calgary's CTrain. He was born in Amber Valley, one of Alberta's historic Black farming communities. He must have been a precocious thinker with a designing mind from an early age. He eventually studied engineering and became the most influential person on my daily commute that I had never heard of.

The CTrain is one of Calgary's emblematic infrastructure achievements. There is hardly a person who hasn't taken it, seen it, or crossed its tracks. It ascends from the south, like the spine of the city, before branching off to the northeast and northwest corridors, forming a kind of lopsided Y-shape.

Bowen was responsible for the original line from Eighth Street station downtown to Anderson station in the city's southwest. It is typically Albertan: straight and flat for miles before calmly curving toward the mountains. In fact, it is not unlike the light rail map for another prairie city, Minneapolis, which yields to the topography of the Mississippi, producing something of an upside down Y.

As a child growing up in this part of the country, I didn't know anything about Bowen. Would it have mattered? Would it have made a difference? Let me ask you this: did Green Walters make white folks laugh?

Poetry in branding

This brings me to my last Black designer, Green Walters himself. I'm not talking about his strategic use of laughter to make white folks comfortable with his presence. Certainly, that was by design, but I'm referring to another, more regional, more iconic mark he designed: his cattle brand.

We often forget the origins of the term "brand," which used to exclusively mean the symbols emblazoned on the sides of cattle. Since the late 1800s, brands have demonstrated ownership while offering ranchers the opportunity to design a kind of signature mark.

A whole language can be read in these symbols. Cattle brands are read left to right, top to bottom, outside to inside, allowing the reader to articulate names such as "Bar U," "Circle K," or "Four Nines."

This brand, also called "Four Walking Sticks," belonged to Alberta's famous Black cowboy, John Ware (eventually shortened to "Three Walking Sticks"). Its meaning is unknown, though many have speculated.

I asked the expert eyes of Hugh Rookwood for an opinion. Hugh is an accomplished Black illustrator/animator who has produced works for Archie Comics, Darkhorse comics, Mattel, Hasbro and others. He also recently illustrated a children's book on John Ware and now, too, has become a Prairie boy.

Hugh identified the symbols with Ware's business: the four legs of his cattle. Interestingly, Tosin also speculated that the brand was a symbol of steadfast stability for Ware's business. I promise you, these are unique interpretations: they focus on Ware's business identity instead of his size, his strength or his laughter.

If John Ware's brand is unflinchingly practical, Green Walters's is simply poetic. Walters started his own ranch using the "Ox Yoke" brand. The poetry of this brand is in the Biblical allusion to the "yoke of slavery" in which Paul urges the Galatians to resist the slavery of sin and stand up for freedom of Christ. The metaphor was not lost on Walters's ears.

Ultimately, there's nothing funny about the brand this man used. This man who was so identified with a performing comedy just short of buffoonery. This man who was deemed too short, too fat, too old, too Black, too threatening to be in our space unless we can find him too funny.

This man, who I am calling a pioneer designer for the Black Prairies, left a mark that says despite any box you force me into, I have made myself free and will not be entangled in the yoke of your bondage again.

Yours truly, "Laughing" Green Walters.

The Black on the Prairies project is supported by Being Black in Canada. For more stories about the experiences of Black Canadians, check out Being Black in Canada here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Born in Sierra Leone, raised in Alberta, and formerly resided in the U.K. and the U.S., Bertrand Bickersteth is an educator who also writes plays and poems. His collection of poetry, The Response of Weeds, was one of CBC's Best Books of 2020 for Canadian poetry. He lives in Calgary, teaches at Olds College, and often (always, actually) writes about Black history in Western Canada.

POPULAR NOW IN NEWS

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

Trillions of cicadas from Brood X set to emerge

N.B. COVID-19 roundup: Person dies after receiving AstraZeneca vaccine, care home resident has died

Vancouver police open investigation into Jake Virtanen sexual misconduct allegations

DISCOVER MORE FROM CBC

We probably won't reach herd immunity against COVID-19 any time soon, but it's OK, experts say

The dos and don'ts to get the most out of your daily walk

Nova Scotia reports new high of 175 daily cases of COVID-19

New York Rangers fire president Davidson, general manager Gorton

COMMENTS

To encourage thoughtful and respectful conversations, first and last names will appear with each submission to CBC/Radio-Canada's online communities (except in children and youth-oriented communities). Pseudonyms will no longer be permitted.

By submitting a comment, you accept that CBC has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any manner CBC chooses. Please note that CBC does not endorse the opinions expressed in comments. Comments on this story are moderated according to our Submission Guidelines. Comments are welcome while open. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Become a CBC Member

Join the conversationCreate account

Already have an account?